Meaningful exhibits

Bezoar stones are found in the stomachs of animals such as antelopes, gazelles and llamas. They are comprised of calcareous substances and matted hair. For a long time there was a flourishing trade in bezoar stones as it was believed they worked as a powerful antidote to poison. Kings and other prominent figures who were afraid of being poisoned carried bezoar stones mounted in gold pendants which they could drop into any potentially poisoned drink for protection. Their rarity and supposed powers made bezoar stones a popular collectors’ item in cabinets of curiosities in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Vrolik collection, before 1830

The oldest objects in our collection are two bladder stones, mounted in metal. The smaller of the two (not pictured) bears the following inscription: “On 27 December 1588 Jan Jacopsen Dick, alias Schot, died at six in the morn. From his bladder this stone was cut – weighing just over a pound forlorn.”

We learn from the inscription on the other stone (which is pictured here) that it was removed on 6 May 1608 from a certain Elisabeth Fransen, aged 52 years, who died shortly after the operation. Bladder stones are comprised of a range of crystallised minerals in the urine and usually start out as kidney stones which then pass into the bladder. Infections and incomplete emptying of the bladder can result in them reaching a considerable size. Bladder stones were traditionally removed by a stonecutter. It was a painful procedure which was often unsuccessful, as these inscriptions testify. If stone sufferers survived the surgery, they were often left incontinent for the remainder of their life.

Hovius and Vrolik collections (photo)

Cyclopia is a congenital disorder in which the normal development of the brain in two halves is disrupted. As a result, the central parts of the brain and the associated body parts, such as the facial bones and nose, fail to develop properly. The eye sockets, which normally develop on either side of the face, are fused into a single central eye. Cyclopia is a malformation that can occur in all vertebrates, including humans. Museum Vrolik houses several cases of such stillborn children with cyclopia. The fact that most congenital malformations could occur in both humans and animals was an important observation to Vrolik. It meant that they resulted from the same sort of disruptions in the forces that – to him – governed growth and development of humans and animals. Willem Vrolik received both malformed lambs from the surgeon Cornelis van der Boon (1785-1858) from Noordwijk. The two lambs came from the same litter.

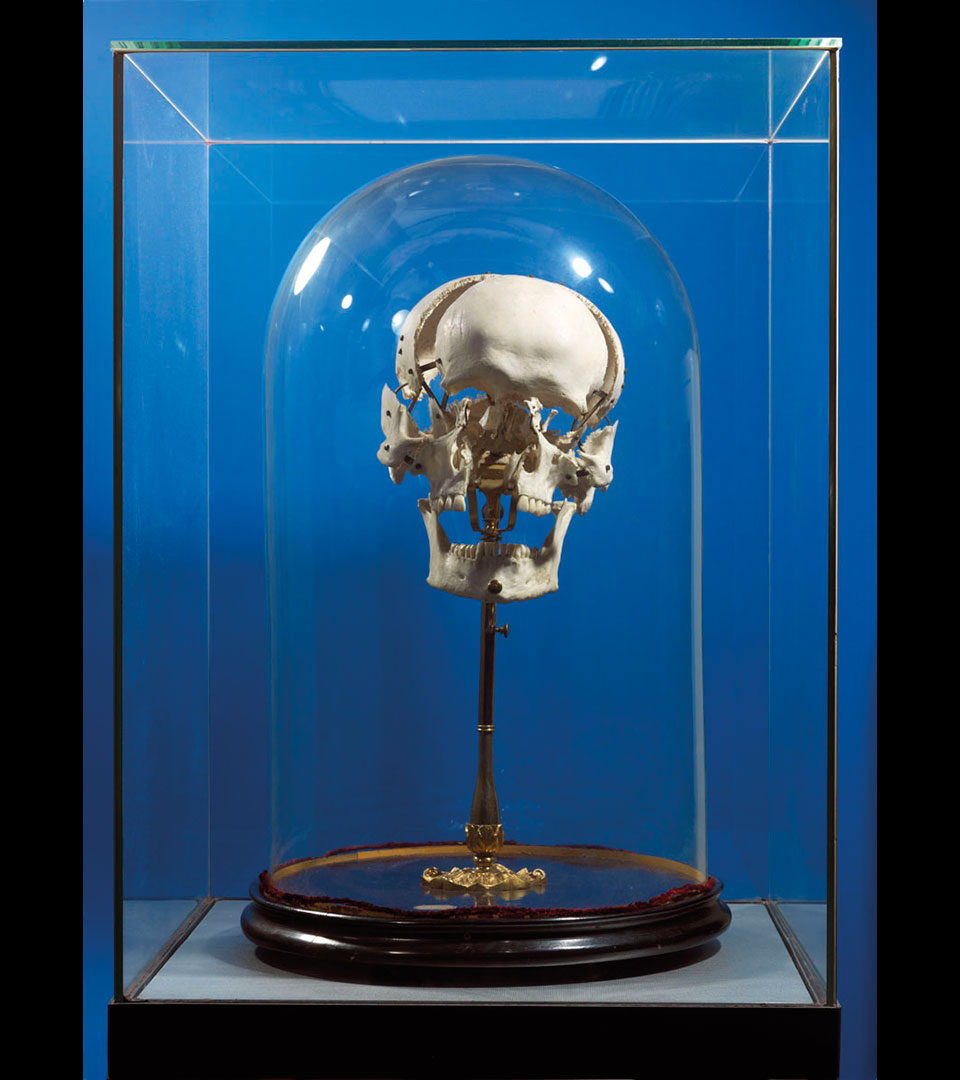

Vrolik collection, first half of the nineteenth century

Human skull in which all of the cranial and facial bones have been taken apart and reassembled using brass plates and screws. The cranial bones are normally joined by sutures, somewhat similar to a zip fastener.

The way in which these bones have been separated and reassembled using brass, is called ‘methode Beauchêne’, after the French anatomist E.F. Chauvot de Beauchêne (1780-1830), who developed this technique. The best known suppliers of Beauchêne skulls were the Parisian maison Vasseur-Tramond of P.N. Vasseur (1814-1885) and his son-in-law G.P.J. Tramond (1846-1905), who supplied teaching aids to anatomical institutes around the world. They received the human skulls and skeletons from the Parisian medical school. Vasseur and Tramond not only sold human Beauchêne skulls, but also of all kinds of animals. Museum Vrolik has eleven of these mounted skulls of animals in its collection. This human Beauchêne skull was purchased between 1865 and 1878.

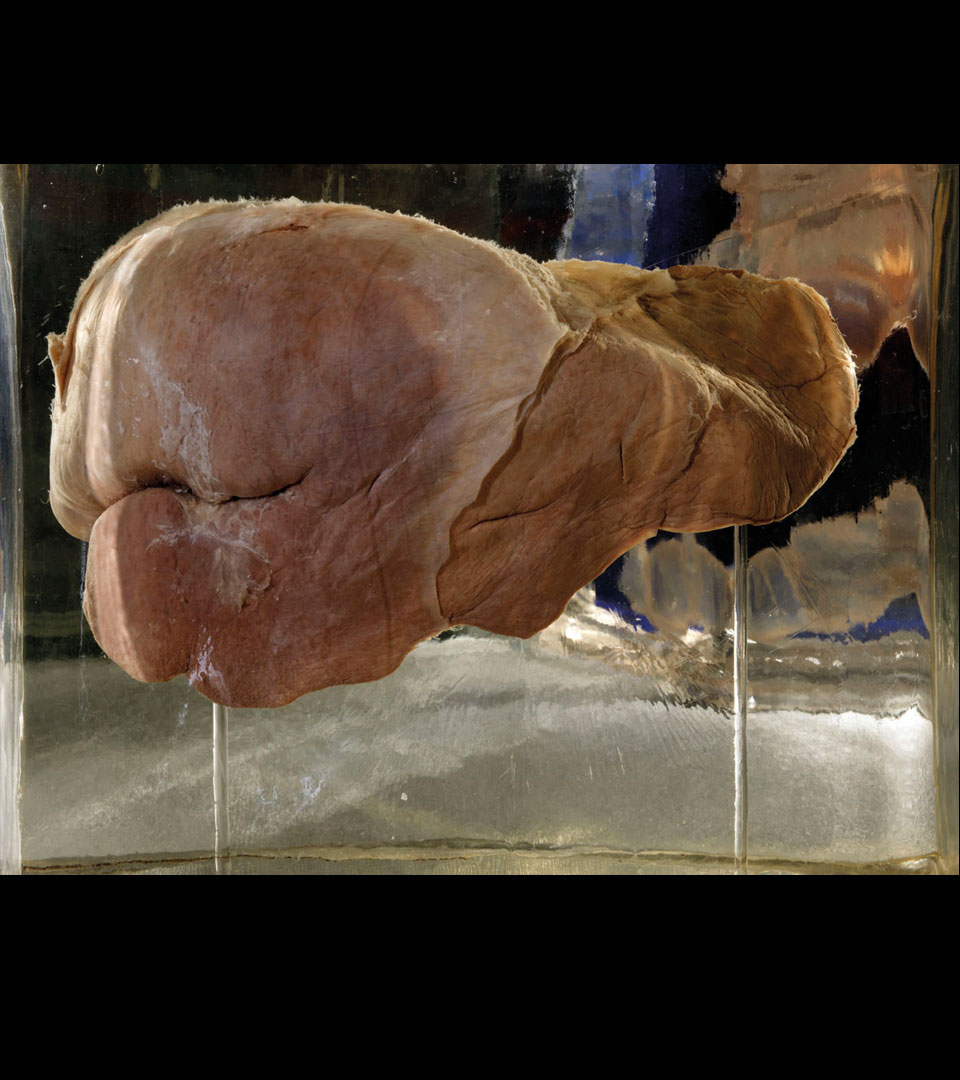

Berlin Collection

A liver, deformed by the wearing of a corset. Corsets were worn – mainly by women – in the nineteenth century to enable them to achieve a fashionably small waistline. When worn over a long period of time, tightly laced corsets could cause malformation of the ribcage, lungs, midriff and liver. Tightlacing of the lungs and midriff could lead to breathing difficulties, but although the liver was deformed, its function was not affected by the wearing of a corset. Corsets came in all shapes and sizes, meaning that the way they deformed the liver also varied. The middle specimen shown here was almost divided in two by the corset (see the large indentation on the left-hand side).

Bolk collection, 1923

Rickets is a twisting and deformation of the bones which is caused by a deficiency of vitamin D, a substance which the human body obtains through ingested food or makes through exposure to sunlight. In the nineteenth century, rickets was a common affliction among poor and rich urban populations – the poor saw little sunlight due to (among others) their long workdays in factories, and the rich often wore clothing that covered their body entirely. The middle class was mostly spared. It did not cause many deaths, except for amongst pregnant women. Softening of the bones caused the spine to collapse in the pelvic opening, resulting in such obstruction that women were unable to give birth. This was often discovered too late, resulting in all manner of complications during labour – the child usually died and the emergency interventions by the physicians often led to puerperal fever. This made rickets a common cause of death of mother and child in the nineteenth century. It is no coincidence that the collection of Gerard Vrolik contains a large number of female pelvises of rickets sufferers.

Vrolik collection, before 1830

This is a skeleton of a lion which was part of the live animal collection of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, King of Holland from 1806 to 1810. In 1809 this collection was housed in the Amsterdam Hortus Botanicus (botanical gardens), of which Gerard Vrolik was director. When the lion died, Gerard Vrolik received permission to dissect it and keep the skeleton. The lion skeleton occupies a prominent place in the so-called ‘chain of life’, a succession of skeletons and skulls of vertebrates. Father and son Vrolik were convinced that all living beings were created in order, in a sort of ladder or chain which progressed from the least perfect to the most perfect animals — in this case from fish to apes and finally man.

Originally from the Vrolik collection; on loan from Naturalis, Leiden

A plaster cast of the hand of a ‘giant’ from Japan. Gigantism or acromegaly is a growth disorder in which excess growth hormone is produced by the anterior pituitary, an organ just below the brain. This excess production of growth hormone is usually caused by a pituitary adenoma, a non-cancerous tumour in the pituitary. Possibly, the plaster model was cast from the hand of the famous Japanese sumo wrestler Ikezuki Geitazaemon (1827-1850).

Vrolik collection, between 1840 and 1860

Femur crushed by a wheel of a heavily laden cart. The bone was probably caught between the spokes of the moving cart and the movement caused a complex fracture. According to anatomist Andreas Bonn, who described all the bones in the cabinet of Hovius, the muscles were torn but the skin remained intact. The leg is a prime example of what would probably have been an everyday accident in the eighteenth century, when the horse and cart was a common method of transport. From the extent to which the fracture has healed, it can be concluded that the man lived for about two years after the accident—although he must have walked with a serious limp.

Hovius collection, between 1770 and 1781

Skull of a man who was disfigured by a kick from a shod horse. The anatomist Andreas Bonn tells us that the horse kicked out at this man in June 1750. As a result of the incident, the man’s cheekbone was broken. After a while his face began to swell, the swelling gradually expanded until it reached from his nose to his temple. The eye became blind and bulged out of the eye socket. According to Bonn, nineteen years after the accident, the swelling burst and the man died.

Hovius collection, 1770

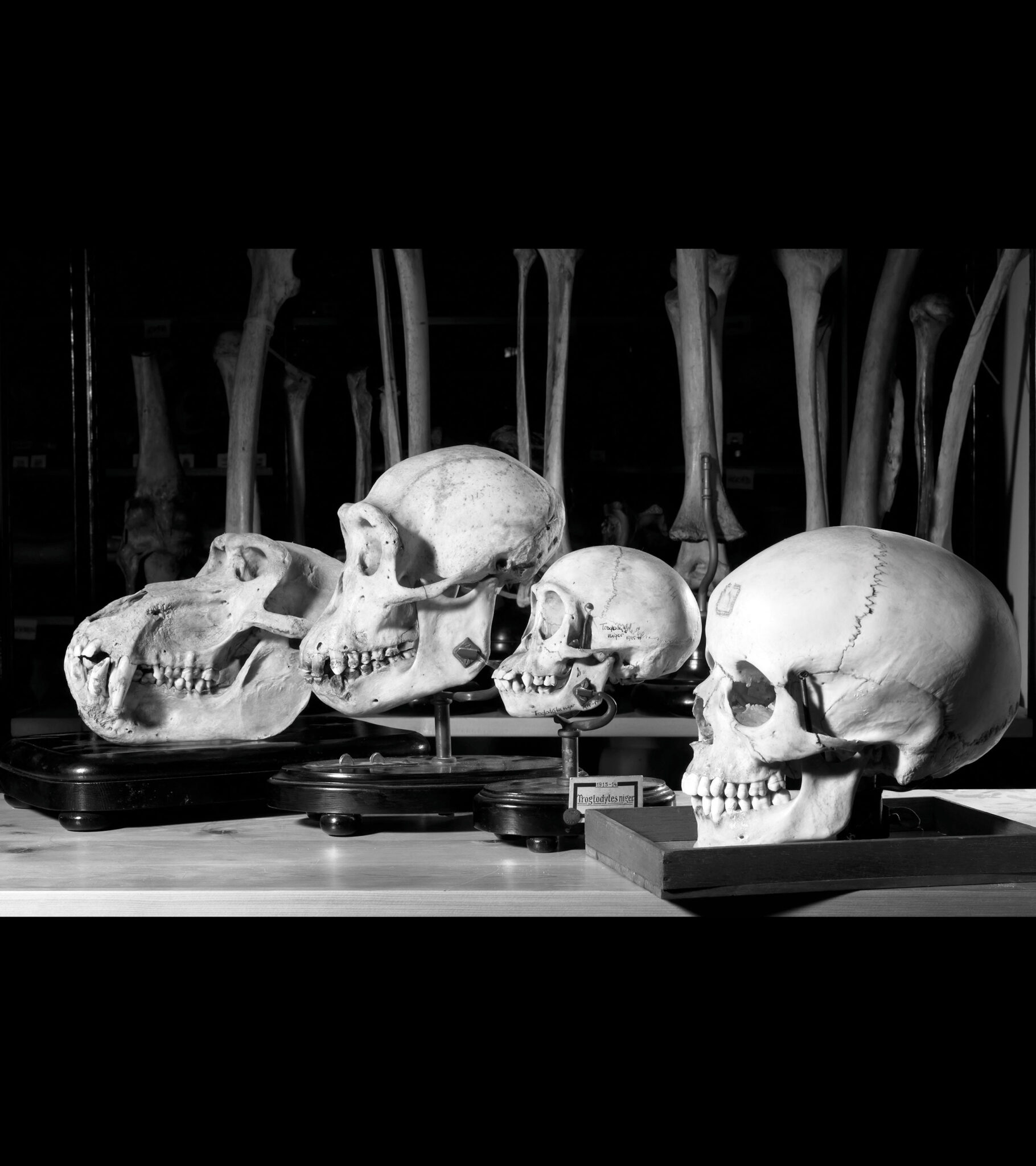

Skulls from a baboon, an adult chimpanzee, a young chimpanzee and a human from the craniological collection of the Amsterdam anatomist Lodewijk Bolk. Bolk became fascinated in the evolution of man. How did man evolve from an ape-like ancestor? Bolk compared skulls, skeletons and specimens from humans and apes and made the remarkable observation that the human body, and particularly the construction of the skull, showed far more similarities to that of young apes than adult apes. From this, Bolk concluded that man must have evolved from an ancestor whose build had remained that of a child, but who was able to reproduce. In Bolk’s words: “man is a sexually mature ape foetus”. Bolk called his theory the foetalisation theory.

Bolk collection, between 1910 and 1930

Plaster cast of the Piltdown skull, one of the greatest scientific hoaxes in history. The fossil remains of the skull, a piece of cranium and a half a jawbone, were found in a gravel pit in Piltdown, England, in 1910. The find was immediately declared ‘the missing link’ in human evolution. Plaster reconstructions of the entire skull were made right away, and these found their way across the whole scientific world. Museum Vrolik also bought one in 1924. Even though there were doubts from the beginning regarding the skull’s authenticity, the hoax was not actually exposed until 1953, when the cranial bones were shown to have come from a medieval man and the jawbone from an orang-utan.

Bolk collection, 1924

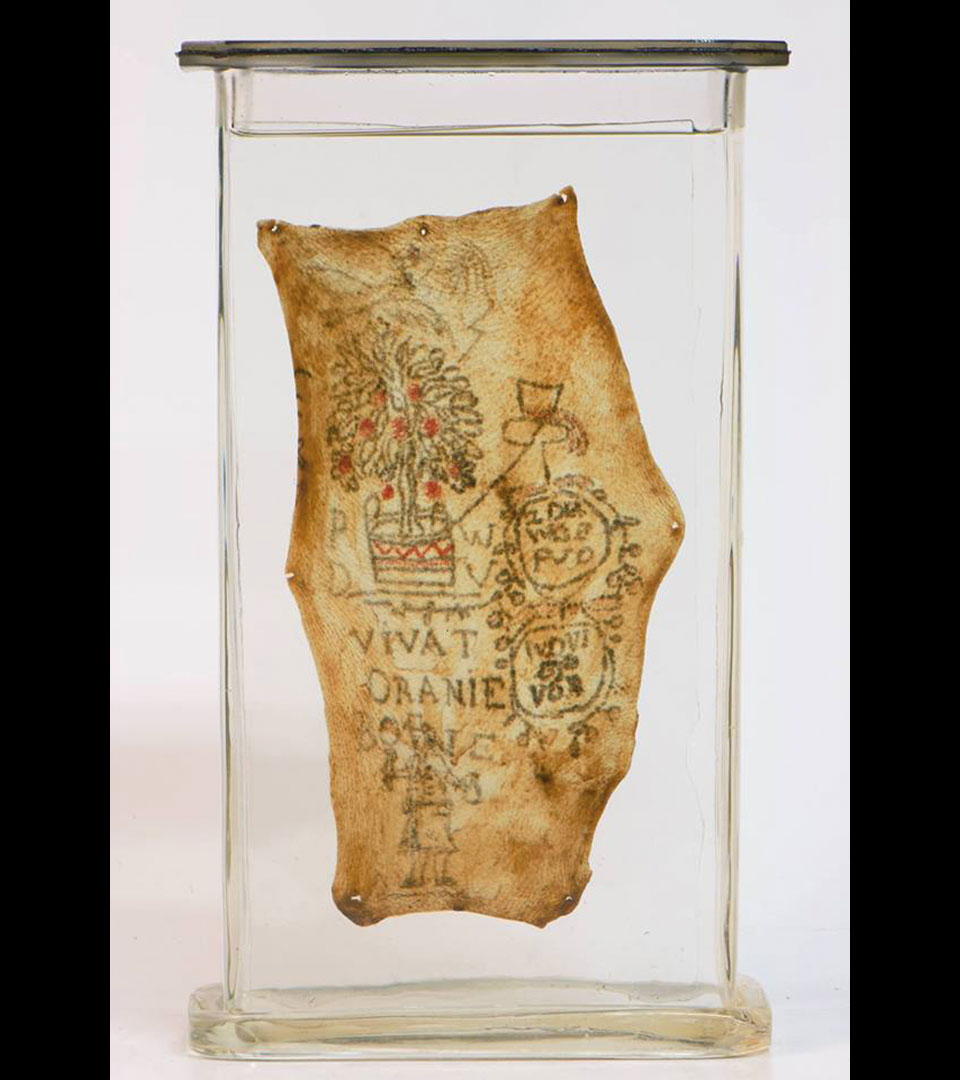

Specimens of tattoos are more a document of their time than an anatomical preparation, particularly if the tattoos contain dates or text. A tattoo with the text “Atjeh 1873-74” refers to the Aceh War. This was a protracted military conflict between the Dutch East Indies army and the Aceh sultanate in the north of Sumatra, which until then had not been under Dutch colonial rule. The owner of the tattoo served in this war. He died fifty years after getting it.

Bolk collection, 1924

The tattoo ‘Vivat Oranien’ with the orange tree dates back to the first quarter of the nineteenth century. It may be a reference to the period around 1813, when the Netherlands became a sovereign kingdom with the coming of William I. After all, these ‘apples of orange’ (Dutch: appeltjes van oranje) symbolize the Dutch royal family. Another possibility is that it refers to the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries—the Batavian Republic and French era—when the Patriots (who were republicans) waged war against the Batavians (who were monarchists).

Vrolik collection, between 1800 and 1830

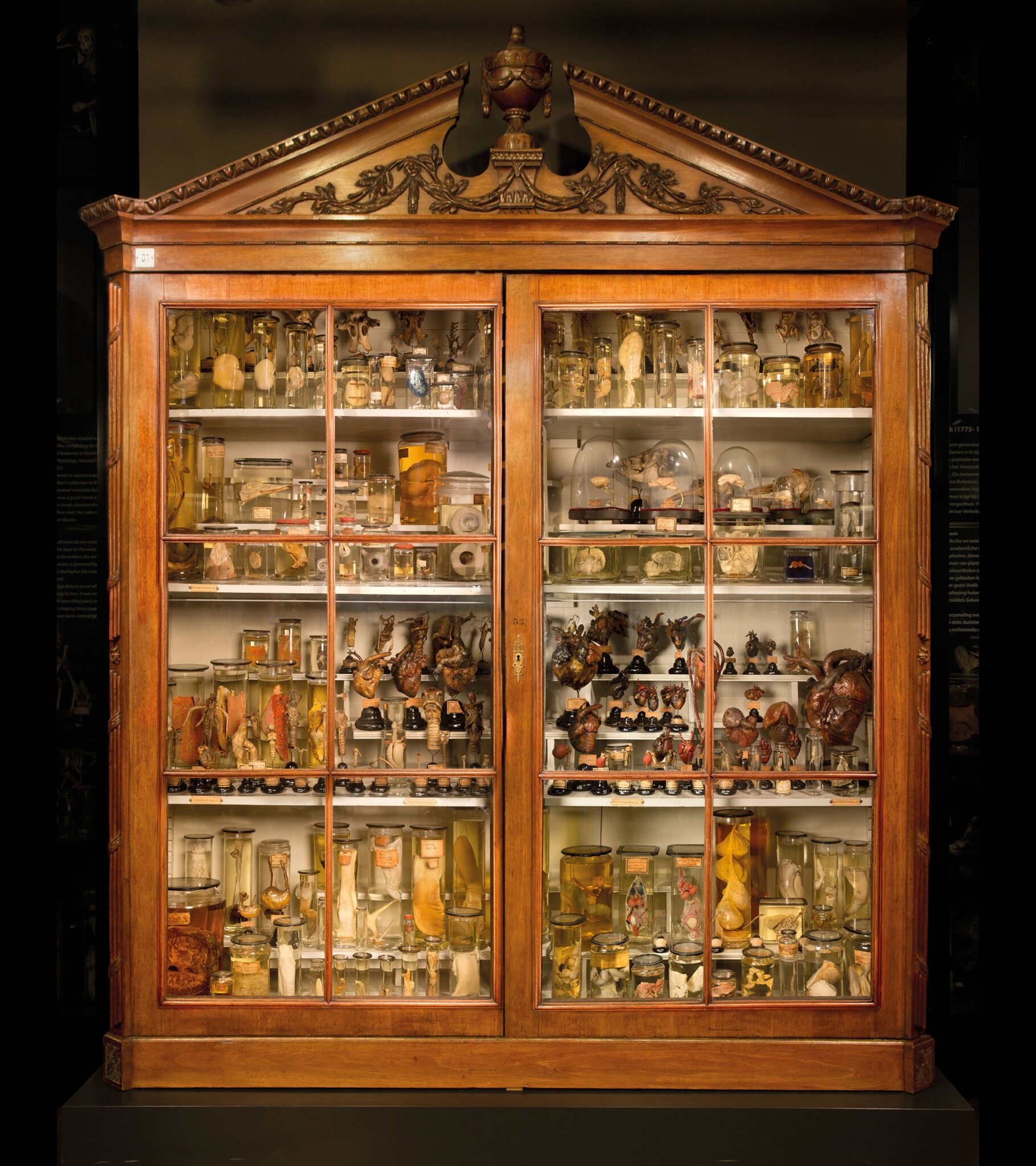

An eye of a whale, a lion heart, a giraffe tongue and many more organs from a wide range of animals. Willem Vrolik in particular was interested in animal anatomy (zootomy) and preserved the organs of just about every animal that he dissected—either dried or in spirits. This resulted in an extensive collection of what is called ‘comparative anatomy’: comparing the same organ from different animals gives one insight into the similarities and differences in build between all these animals.

Vrolik collection, between 1800 and 1863

Thanatophoric dysplasia: a hereditary defect in the ossification of cartilage during foetal development, which in this case has resulted in malformation of the skull as well as shortening of the bones. Infants with this type of malformation usually die at birth. Willem Vrolik received this stillborn infant from the Amsterdam surgeon and obstetrician Petrus Weisz. Vrolik collection, between 1840 and 1848

Cephalothoracoileopagus: the skeleton of conjoined twins linked at the head, chest and abdomen. Infants who are fused in this way usually die at birth. Willem Vrolik received these stillborn conjoined twins form the French ophthalmologist Ch.J.F. Carron du Villards (1801-1860). The twins probably came from Paris. Vrolik collection, around 1845

Osteogenesis imperfecta (type 2b, Vrolik’s disease): the name means literally ‘imperfect development of the bone’. It is a hereditary defect in the bone development caused by the disrupted production of collagen. Without this collagen the skeleton is very fragile: a foetus with this disease can suffer broken bones from the tiniest movements in the womb. These fractures heal, but the bones become seriously deformed. Willem Vrolik received this skeleton from the Amsterdam surgeon and obstetrician D.J. Griot La Cave. Vrolik collection, before 1840

Sirenomelia: sirenomelia is a congenital deformity that is very reminiscent of a siren (a creature from Greek mythology) or mermaid in form. There is only one leg, which sometimes ends in one foot, sometimes in two feet, but is often footless. Usually children with this defect die at birth. Willem Vrolik received this skeleton with sirenomy from the Groningen professor of obstetrics Jacob Baart de la Faille (1795-1867). Vrolik collection, between 1832 and 1840

Anencephaly: skeleton of a newborn child with anencephaly. Failure of the neural tube (the embryonic precursor of the brain and spinal cord) to fuse means that the brain has not developed, and therefore nor has the section of the skull above the face. Infants with anencephaly usually die shortly after birth. The origin of this skeleton is unknown. Vrolik collection, between 1800 and 1863

Thoraco-ileopagus: the skeleton of conjoined twins linked at the abdomen and the tip of the sternum. Willem Vrolik examined and described these twins and concluded that they were conjoined in exactly the same way as the ‘Siamese twins’. This was the name given to the conjoined brothers Chang and Eng Bunker (1811-1874) who were born in Siam (Thailand). Chang and Eng travelled around the world and became so famous as the ‘Siamese twins’ that after their death, the term came to be used as a synonym for all conjoined twins. Vrolik collection, before 1840

A stone fruit or lithopaedion begins as an ectopic pregnancy in the abdominal cavity. If the embryo is able to access a capillary network, it is able to obtain sufficient nutrients and oxygen from the mother’s blood in order to grow. If the foetus dies prematurely in the abdominal cavity, then the mother’s body can encapsulate the foetus in connective tissue, after which it dries out and hardens (calcifies). This results in a stone fruit or lithopaedion, literally a “child of stone”. A stone baby can go unnoticed for years. The phenomenon occurs in humans and other mammals. An example of a human lithopaedion can also be seen in Museum Vrolik.

Vrolik collection, around 1855